In Our Own Spaces #9: "Bring a Work in Progress"

Intentions for a community hosted artist salon series

The following writing was created for and spoken at the ninth edition of the community-lead and hosted artist salon series “In Our Own Spaces” on January 18th, 2025. My partner and I founded this salon series as a space for communal gathering, radical conversation, and redefining uses of art in our current society.

Earlier this week as I arrived for a yoga class, the man next to me was sharing his experience evacuating from the West Hollywood Sunset fire. He lamented how, after instructing his two children to pick one thing they wanted to bring (outside of the essentials he and his wife were grabbing, of course), they both came back with the largest box of legos they could find. He couldn’t see how this easily replaceable jumble of plastic could possibly mean so much to them, and wanted to urge them to think about what they truly cared about, but his wife put her hand on his shoulder and encouraged him to accept their decision. Children aren’t thinking about their things the same way we are. Maybe a 20 or 30 year old version of them would regret leaving grandma's hand-knit scarf to disintegrate into ash, but in the heat of the moment, these kids grabbed something that they likely use every day. The importance of these items lay in their utility, not their replaceability.

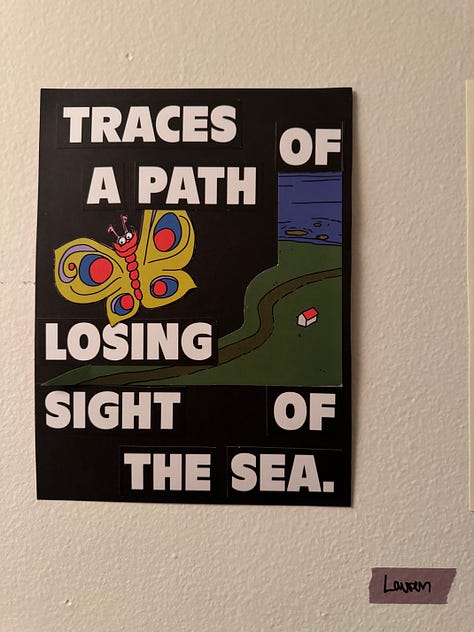

My instructor responded to this story with one of her own, of a friend (or acquaintance, undetermined) who lives in the palisades. After arriving in Santa Monica with his family, he found himself unable to bear the thought that he may never see his home again. He left his kids and partner at the hotel and drove back to his beloved home, hosing off his house and yard, and carrying buckets of pool water around his neighborhood for days, putting out small fires to prevent their growth. Unlike unlucky others, he survived and with him 5 homes that otherwise would have been destroyed. I kept quiet, thinking to myself that it was the dumbest decision one could possibly make. How could you risk your precious life for these worthless things? I shared this story with Lauren, expecting her to have this same response, and was surprised to instead hear that she understood the urge, seeing his actions not as idiotic, but brave. She reflected on our own departure where, in the midst of panic, she didn’t think to grab even one sketchbook. If our home had been destroyed, her entire body of work would go with it.

Something that has become really visceral for all of us over the past few weeks is how “the crisis” acts as an arena in which what is important to us becomes very salient. We go about our life worried about this and that and whatever daily annoyance pops up to interrupt our flow and plans. Those little things hold real weight in our daily lives. Some (existentialists) would argue that all of this daily drama is nothing more than a distraction from our real problems: death, isolation, freedom, and meaning. It takes an event in which we are faced with our own mortality to recognize our paradox as the meaning-making being in a meaningless world.

This time of year exhibits a great example of how we attempt to do this: the new year's resolution. Even in our ritual-deprived culture, this tradition has remained a staple, colorfully scripted into bullet journals and plastered across social media feeds. As religious affiliation has fallen and cognitive dissonance risen, how have these resolutions stood the test of time? If we look at the content of most resolutions, we can start to see how they fit into our materially-rich and spiritually-poor culture. Common new year’s resolutions may include: lose [x] pounds, stick to my budget, stop smoking, work out every day. Material, measurable goals. These aren’t bad goals, but we don’t stick to them! Most of us know that what we really want underlies these superficial task lists. Our focus is drawn to the surface, the symptoms, of the underlying problem: our deeper crisis of making meaning for ourselves.

In his video essay series Awakening from the Meaning Crisis, cognitive scientist John Vervake explains this distraction, or self-illusionment, through the distinction of two psychological states: the having mode, and the being mode, and with them our perceived having needs and being needs. Having needs relate to objects, like a cup with which to hold water, or the water itself, fresh air to breathe, and safe food to eat. Being needs are entirely different, for example, love and connection with other humans, a purposeful life. We cannot have these things, but we can work to create them as a state of being. Our meaning crisis, he supposes, is worsened by the conflation of being needs as having needs, and our attempt to fulfill them through the material (i.e. love with sex, peace with sedation, etc.). This is what we do when creating new year’s resolutions that we can possess, rather than intentions that we can embody. Vervake asks “you put so much effort in developing your finances, your body; how much time have you spent lately developing your character?”

Our inclination to create goals for ourselves is a worthwhile task. Humans, of all creatures, have a powerful ability to engage with selective attention. When we decide what is important to us— our value system, our preferences, our desires— we start to create our reality around it. Douglas Hofstadter, creator of Strange Loop Theory, notes that “in the end, we are self-perceiving, self-inventing, locked-in mirages that are little miracles of self-reference.” All living things have a self-creating quality, like the leaves of a tree which consume sunlight to provide energy to the tree so that the tree can create more leaves. But to what end? This cycle has to start somewhere, and that is in the seed of the tree which contains nothing but the potential energy needed to be a tree. The end is being a tree, making more seeds for more trees to be trees. It’s a loop.

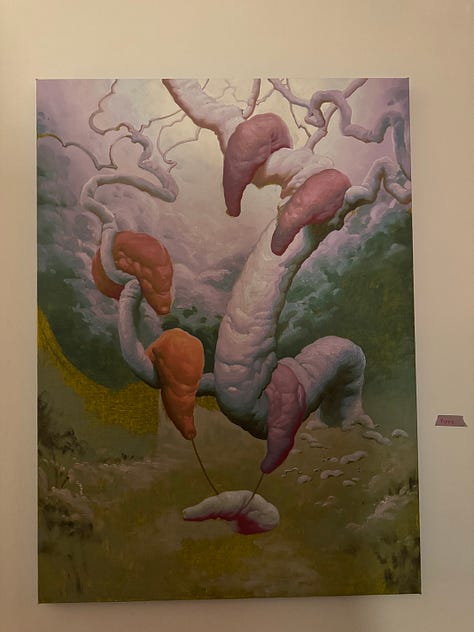

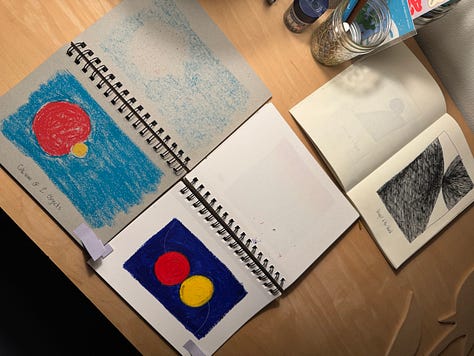

This is why each year, we keep coming back to this salon theme: bring a work in progress. How unsatisfying is it to complete an artwork? It makes so obvious the distinction between that and I; this artwork which gets to be complete, which does not require of itself anything more, which is inherently being: complete and full of meaning. And in that moment when the artwork is complete, I can no longer interact with this object in a way that defines myself as being an artist, I just have an artwork. To be in progress is to be a self-perceiving, self-inventing, self-referencing human always striving to live up to our potential, to find meaning.

Perhaps the legos chosen by my classmate’s children in their flight from crisis act, for them, as a portal which unlocks the being state. Think about the way a lego is used as a tool: it is a building block with which one can create, out in the world, whatever is within their mind (within the limitations, of course, of the physical reality). It enables the creative act, becoming an extension of self in the flow of play. The creative act is a means of being.

Some questions to reflect on these themes for yourself: Where, in your work, do you find yourself conflating having and being needs? How do you allow yourself to be embodied by the creative act? What societal pressures keep you from fully immersing yourself in the creative act?

As always, blessed by the voice of @broca.ray!